The following information will help you to understand and carry out your obligations under the Dja Dja Wurrung Land Use Activity Agreement (LUAA). It was originally developed for use by local government, but is now suitable for general use.

These pages provide general information, not legal advice.

For land use activities on Taungurung Country, read about the Taungurung Land Use Activity Agreement.

Overview

Context: The Dja Dja Wurrung Recognition and Settlement Agreement

The Land Use Activity Agreement (LUAA) is part of a broader settlement package called the Recognition and Settlement Agreement (RSA). This agreement came into legal effect on 24 October 2013.

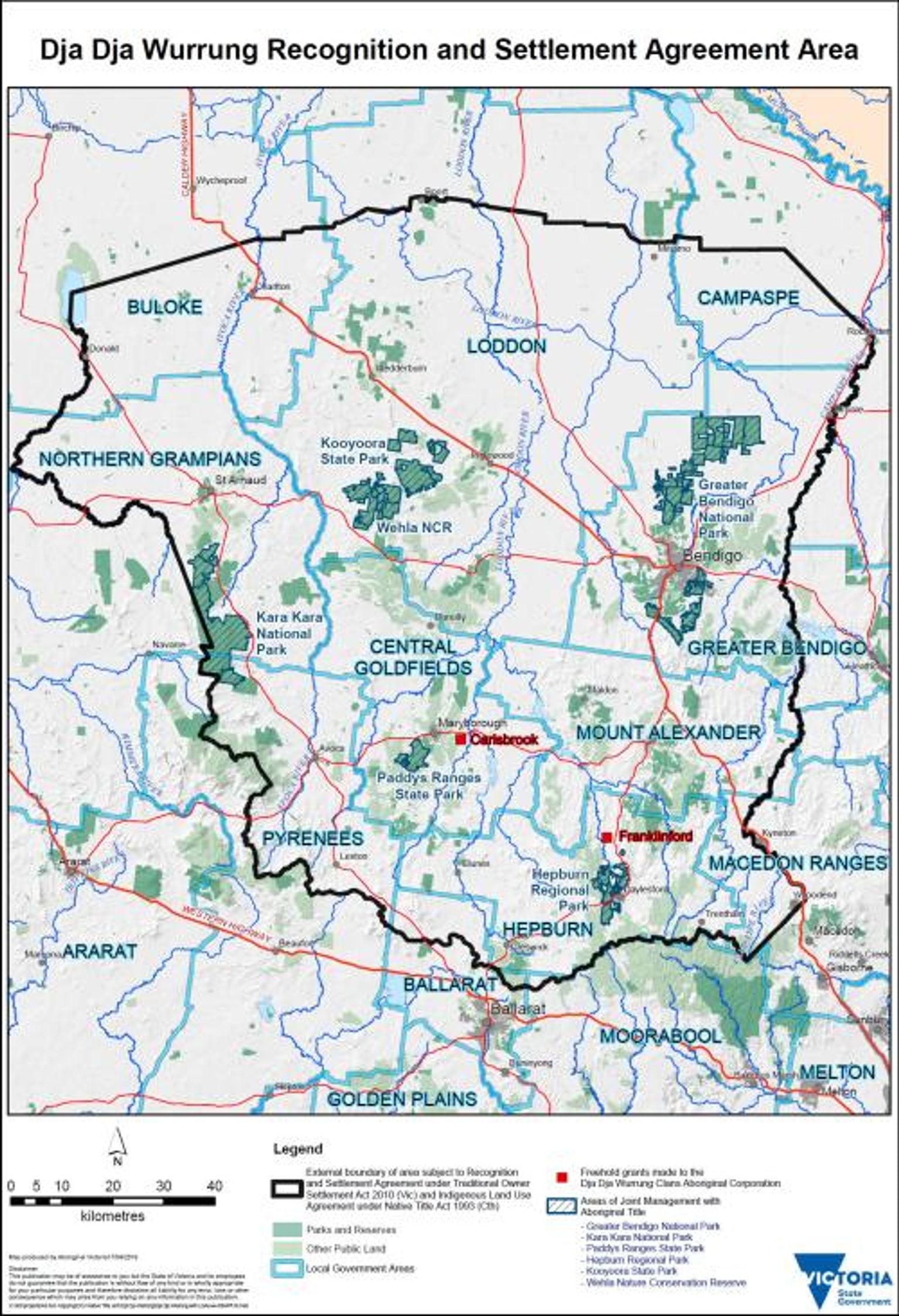

In the RSA, the State of Victoria recognised the Dja Dja Wurrung people as the Traditional Owners of an area of Victoria. A map of this area can be found below.

The RSA is made up of a set of agreements that are legally binding on the State of Victoria, including all government agencies, and on DJAARA (the Dja Dja Wurrung Clans Aboriginal Corporation) as the representative body of the Dja Dja Wurrung people.

These agreements, including the LUAA, recognise and protect the Traditional Owner rights of the Dja Dja Wurrung people. In return, the Dja Dja Wurrung people agreed not to pursue the legal recognition of native title rights that they may hold.

These agreements are complementary with cultural heritage protection – see further information below.

The Land Use Activity Agreement

The LUAA gives procedural rights to the Dja Dja Wurrung people regarding proposed activities on public land (also known as Crown land). The greater the impact of those activities on Traditional Owner rights, the higher the level of procedural rights under the LUAA.

The LUAA replaces the Future Act provisions of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that would otherwise apply. It seeks to provide a simpler and more streamlined approach. Like other parts of the settlement agreement, the LUAA is based on the the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 . Under this Act, proposed activities on public land must comply with the LUAA.

That Act, together with the LUAA, sets out the processes that managers of public land must follow before dealing with public land, or carrying out works on it. Those land managers include departments, statutory authorities, local governments, and committees of management.

Introductory examples

Under the LUAA, each activity on public land needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. These hypothetical examples give you some quick illustrations. Please continue reading these pages for a full explanation.

The LUAA and Aboriginal Heritage protection

As the examples above illustrate, LUAA processes are separate from any cultural heritage protection requirements under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (the AHA).

That legislation continues to apply, on both public and private land. Its requirements are independent of those in the LUAA and the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010.

DJAARA is both the Dja Dja Wurrung representative body for LUAA purposes and the RAP (Registered Aboriginal Party) under the AHA .

DJAARA's procedural rights under the LUAA and the management of AHA matters are complementary and there will be no duplication of processes. DJAARA may raise cultural heritage matters as part of a response or negotiation under the LUAA. However, any issues raised would be resolved through the mechanisms under the AHA.

A new relationship

Many government agencies regularly consult with stakeholders in their communities, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

However, the RSA established a different kind of relationship between government and the Dja Dja Wurrung people as Traditional Owners:

"This Recognition and Settlement Agreement binds the State of Victoria and the Dja Dja Wurrung People to a meaningful partnership founded on mutual respect.

It is a means by which Dja Dja Wurrung culture and traditional practices and the unique relationship of Dja Dja Wurrung People to their traditional country are recognised, strengthened, protected and promoted, for the benefit of all Victorians, now and into the future.”

- Recognition Statement, 2013 (emphasis added)

The LUAA should be interpreted and applied consistently with this commitment to a "meaningful partnership founded on mutual respect".

For example, public land managers have engaged in dialogue with the Traditional Owners when questions of interpretation have arisen, rather than seeking advice from lawyers on how to minimise their compliance.

Such an approach is also consistent with the principle of ensuring the ‘free, prior and informed consent’ of Indigenous people in matters affecting their rights.

The need for compliance

All Decision Makers in relation to land covered by the LUAA must ensure that they are complying with the LUAA. This includes departments, statutory authorities, local governments and committees of management.

Who exactly is responsible for complying with the LUAA?

Local Government authorities can download a tailored adaptation of the above information here.

VCAT can make orders

If DJAARA believes that the LUAA has not been complied with, it can seek orders from the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT). VCAT can determine, or order:

- whether a land use activity was correctly classified

- whether negotiations were in good faith

- whether the reasonable costs of negotiation (which must be reimbursed to DJAARA) were correctly calculated

- to stop, not start, cancel or suspend a land-use activity (including interim enforcement orders in urgent cases)

- to restore land as nearly as practicable to its condition immediately before the land use activity started.

Two key questions

To determine what (if anything) the LUAA requires before a land manager can carry out a “land use activity” on Crown land, there are two main questions:

1. Does the LUAA apply to this land?

- Is the land “public land” (reserved or unreserved Crown land)?

- Is it within the LUAA area?

- Is it excluded from the operation of the LUAA for one of several listed reasons, including the existence of certain kinds of infrastructure?

Read more at Does the LUAA apply to this land?

2. What kind of activity is it?

- Routine: No action needed

- Advisory: Notification and consultation process

- Negotiation: Negotiation process. VCAT and the minister can break deadlocks after 6 months

- Agreement: Negotiation process. The activity can only proceed with DJAARA agreement

Read more at What kind of activity is it?

Each type of activity has specific processes to be followed. These are explained on What's the process?, along with recommended templates you can use.

Dja Dja Wurrung RSA and LUAA area

Next steps

Continue reading: Does the LUAA apply to this land?

Updated