- Inducted:

- 2015

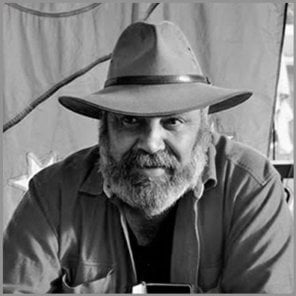

Richard Joseph Frankland is a Gunditjmara man who inspires through his writing, his films and his music.

Born in 1963 Richard is the third youngest of 6 children, and grew up mainly in Portland in south-west Victoria. His father, also named Richard, was a farmer and court clerk of European descent who died suddenly when Richard was 6. As a consequence his mother, Christina Saunders, and her family have had the biggest influence on Richard’s life.

Christina comes from a long line of Gunditjmara warriors. Her father, Chris Saunders served in World War I and her brothers Reg and Harry Saunders served in World War II. Reg was the first Aboriginal to become a commissioned officer and went on to see active service in the Korean War. Harry, who was killed on the Kokoda Trail, was the inspiration for one of Richard’s early films.

Christina herself fought her own battle at home in the 1970s. She and Lorraine Onus prevented Alcoa from building a smelter on Gunditjmara land, taking the case all the way to the High Court of Australia.

He was deeply affected by the families he met and the stories he heard

At the age of 13 Richard dropped out of school and lived on the streets of Melbourne for a few months before finding work in an abattoir, then as an apprentice glazier. After a stint with the Army Reserve he enlisted in the Regular Army in the early 1980s. In 1988 he was appointed as a field officer for the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Over the 4 years he worked in this role, he was deeply affected by the families he met and the stories he heard.

Richard drew on his experiences as a field officer to make the 1992 documentary, Who Killed Malcolm Smith? It received the Australian Film Institute’s Best Documentary award – the first of many Richard has since received for writing and directing. Other work inspired by his Royal Commission experience includes the television drama No Way To Forget (1996) which was nominated for 4 AFI awards and won 2. He also wrote the play Conversations with the Dead (2001), which played at the United Nations, as well as producing 6 albums of songs and over 400 poems.

During his prolific career he has produced over 50 films and documentaries

The diversity of Richard’s work is demonstrated through films such as Harry’s War (1999), which he wrote and directed. Based on his uncle’s experience in World War II, the play explores the idea of what it is to be Australian and the relationships between black and white soldiers. In his other documentaries such as The Innocents (2003), Richard tells of the experiences of children affected by war and violence in Palestine and Mexico. During his prolific career he has produced over 50 films and documentaries.

Richard’s work in film is not restricted to serious topics. His sharp sense of humour shines through in the film Stone Bros which he made in 2009 – a ground breaking Indigenous comedy within the ‘road movie’ genre.

Music is also a big part of Richard’s life. His first band, Djambi, supported Prince on his 1991 Australian tour and since 2000 he and guitarist Andy Baylor have formed The Charcoal Club. Richard’s music features on the soundtracks of many of his films.

Richard is closely involved with land rights and Aboriginal affairs generally

When he is not writing plays, making films or music, Richard is closely involved with land rights and Aboriginal affairs generally. In 1994 he founded the Mirimbiak Nations Aboriginal Corporation, a body set up to represent and assist community groups to lodge native title claims in Victoria. Richard’s strong connection to his traditional lands is expressed in his 2006 documentary The Convincing Ground, which looked at the effects of land development on a site near Portland which is sacred to the Gunditjmara.

Richard’s dissatisfaction with the federal government’s abolition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) led him to form the political party Your Voice for which he stood as a Senate candidate in 2004.

Since 2011, through Koorreen Enterprises, Richard has been running workshops for community, business and government groups on lateral violence and cultural safety. Having seen what years of oppression have done to many Aboriginal communities, his workshops aim to facilitate better problem-solving, as well as encouraging freedom of cultural expression. This work has been recognised by the Australian Human Rights Commission and Richard now trains others to undertake these workshops.

Focus on Australian Indigenous peoples’ cultural and community foundations

In 2014 Richard collaborated with the Melbourne Theatre Company on a production about his own life. Titled Walking into the Bigness, the production was a celebration through stories of Richard’s life as an activist, writer, filmmaker and musician.

Despite leaving school at the age of 13, Richard has notched up many academic achievements. In 2007 he completed his Master of Arts at RMIT University with a thesis entitled ‘The Art, Freedom and Responsibility of Voice’ and in the same year published his first novel, Digger J Jones. The book, which is partly autobiographical, tells of a young Koori boy growing up in 1967 at the time of the Referendum which gave Aboriginal people citizenship rights. He has also written another children’s book, The Naming of Yellow Hair, which addresses the diversity of Aboriginal skin colour. In 2015 Richard was appointed Head of Curriculum and Programs at the Wilin Centre, Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne. He is now embarking on a Higher Doctorate Degree at the University of Melbourne, focusing on Australian Indigenous peoples’ cultural and community foundations.

When Richard Frankland is not teaching, mentoring, writing, directing, filming or singing, he lives with his partner Steph Tashkoff and his 2 children Nakaya and Taram near Portland. His mantra ‘We are not a problem people, we are people with a problem and that problem was colonisation,’ continues to inspire and motivate him.

Updated