- Inducted:

- 2022

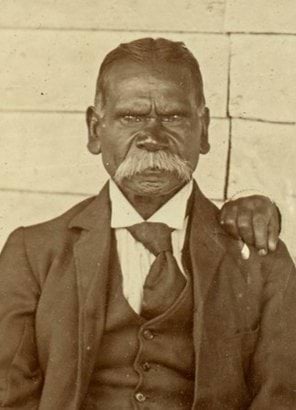

Collin Hood was born circa 1836 near Hexham in Djab Wurrung Country, southwestern Victoria. His parents were King Blackwood and Mary, and they gave him the name, Merrang. His personal totem was Jallan, the whipsnake.

Over the course of his seventy-eight years, Collin faced many adversities and personal tragedies. Despite these hardships he remained a visionary leader—first, for the Eastern Maar people in the west of Victoria and then the Gunaikurnai people in the east of Victoria.

In 1855 at the age of 19, Collin married Ageebonyee, the daughter of Ningi Burning and Nango Burn. Ageebonyee had learned to read and write as a domestic servant for a settler family and took the English name of Nora Villiers two years prior when she was baptised approximately the same time Merrang became a farm hand and stockman in the area.

The original squatters of the Hexham area named their property Merrang, and when the Hood family purchased it in 1856 they retained the name. Collin was 20 years old when the Hood family purchased the property and he continued to work for them as a stockman. Collin assumed the Hood family name soon after, along with the first name of Collin. Station records show that Collin Hood was paid an equal wage to non-Aboriginal farm hands and was one of their most trusted and respected workers.

In 1860, Collin and Nora Hood were reputedly the first Aboriginal couple in western Victoria to apply for a government grant of land, hoping to establish themselves as farmers. Their request was initially approved and then revoked, effectively forcing them to move to the Framlingham Aboriginal Reserve (Framlingham) in 1865. They had six children together before Norah died on 28 March 1871 at the age of 35.

In August 1872, at Framlingham Collin married Louisa Lutton, née King (or Tappoke), widowed daughter of ‘King George’ and Mary. Born near Mount Rouse, and with three children, she and Collin had a further four children together over the next eighteen years.

Collin again proved himself to be a hard and reliable worker at Framlingham, becoming head stockman by 1880. He was by then an acknowledged Elder and spokesman for the Framlingham residents. When the Aborigines Protection Board took the decision on 7 August 1879 to close Framlingham, Collin Hood was one of two Aboriginal residents who on behalf of all residents protested to the Victorian Chief Secretary (Premier), Alfred Deakin.

Collin stated that the area had been their hunting grounds, that they hoped to be allowed to live there for the remaining years of their lives and if removed to other places would not agree. Collin then firmly indicated that if the decision was taken to close Framlingham they would all sit down and refuse to move.

The Aborigines Protection Board’s acting general inspector Reverend Friedrich Hagenauer had visited Framlingham and claimed its residents “... had been crammed in the idea of getting a few hundred acres of land from the reserve, either as a hunting ground and small farms, and their leader Collin Hood seems very earnest in his request. But few [residents] are locals, some have already left, and the rest will soon follow”.

To correct this deliberate falsehood, the settler Robert Hood encouraged Collin to make a list of the residents and their origins. This was so he could have it published and gain public support for their cause. A list was then prepared by Collin and his daughter, together with Robert, and they published it in the local Warrnambool newspaper. This list of 39 residents showed that all bar one person was born in the district.

The facts collected were then used by the Victorian Member of Parliament, John Murray, to argue in Parliament against the closure of Framlingham. This manoeuvre showed Collin’s political acumen, as John Murray was an astute politician who would later succeed Alfred Deakin as Premier of Victoria. In October 1890, as a direct result of John Murray's advocacy, Alfred Deakin announced 500 acres of Framlingham land would be permanently retained as an Aboriginal Reserve.

With the fight to save Framlingham won, there was now nothing to keep Collin there. His wife, Louisa, had died that year and his children now lived in Gippsland. So, in early 1891, Collin moved to Ramahyuck Mission and from there moved to Lake Tyers Mission (Lake Tyers). On 17 March 1898, now aged 61, Collin married the 23-year-old widow, Helen Rivers, at Lake Tyers. Collin and Helen (née Johnson) were to have four sons and a daughter together.

For the whole of the twenty-two-year period he spent in Gunaikurnai Country, Collin continued the leadership role he had started in Eastern Maar Country.

Collin died on 3 May 1914 in his seventy-eighth year, with a proud legacy as one of the very first land rights activists in Victoria. As a testament to this legacy, both the Lake Tyers and Framlingham communities gained ownership of their land 56 years later as part of the Aboriginal Lands Act 1970. This would not have been possible without Collin’s advocacy.

To this day, the Hood family remains highly respected in both Eastern Maar and Gunaikurnai Country, with many of Collin’s descendants proudly continuing his legacy.

Photo source: University of Melbourne Archives. Image reference 1976.0013.00114

Updated